In 2016, London’s Pigeon Air Patrol took to the skies, tweeting (literally, in the human sense) geolocated pollution readings from tiny Internet-connected sensors strapped to their backs. As the pigeons fluttered their way across the city, their environmentalism struck a nerve and went viral on social media. These valiant patrons of public space were calling on Londoners to act on the city’s mismanagement of perhaps its most valuable public good: clean air.

Heightened air pollution exposure is linked to chronic lung and heart disease, cognitive impairment, reduced birth weight, and lower lung capacity in children. Importantly, areas with high COVID-19 death rates also happen to have higher air pollution burdens, and new research suggests that long-term exposure to air pollution may be a fatal precondition.

As an environmental economist studying air pollution, I think back to London’s Pigeon Air Patrol more often than most. Their cute little backpacks were, and still are, one of the most brilliant ways of raising air pollution awareness I have ever seen. They also point to a potential solution for our contemporary air control problems: citizen air quality monitoring. The emergence of highly accurate low-cost sensors enables us to reimagine our future with democratized air pollution control.

Four years after the pigeons first took flight, I am left wondering if and when we too will wear air pollution sensors and what that near future with widespread personal air monitoring might look like.

Before I began my studies, I associated air pollution with images of opaque skies at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. I thought serious air pollution was a far-off concern – one that I was removed from by no less than a hemisphere. That turned out to be a misperception.

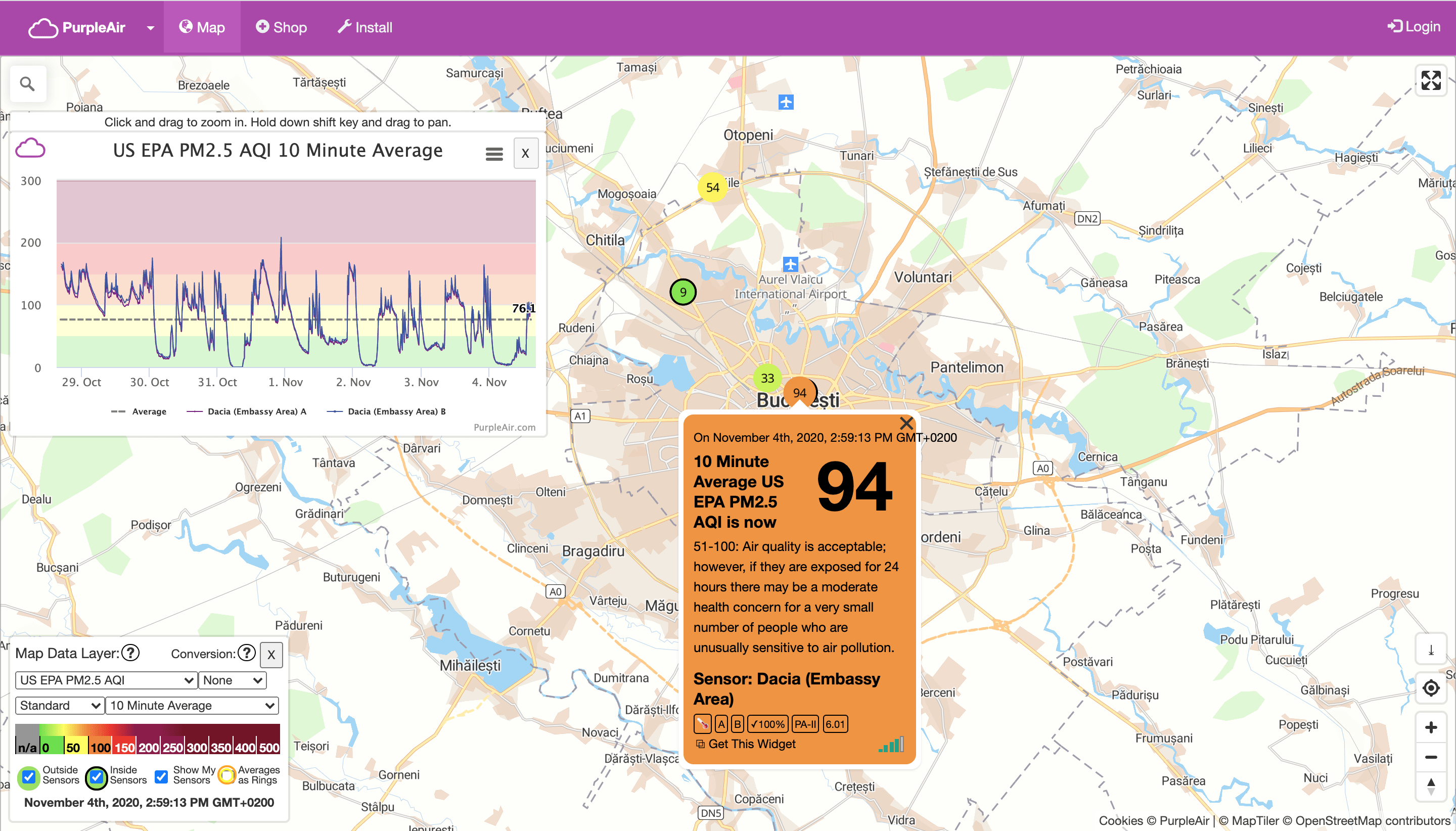

Across 432 European cities, social damages from air pollution are estimated to exceed 166€ billion annually, costing the average European city dweller over 1,250€ annually. In Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland, the social welfare loss from air pollution is comparatively high, as damages approach nearly 10 percent of average income levels. Residents of Romania’s capital Bucharest experience the highest total costs (6.35€ billion) from air pollution of any European city, with the exception of London (11.38€ billion).

The vast majority of air pollution’s social costs are health-related: increased mortality and morbidity. Air pollution annually causes nearly 400,000 premature deaths in the European Union and over 7 million globally, according to the European Environmental Agency and the WHO, respectively. One tenth of all deaths can be traced back to poor air quality.

Economists increasingly find evidence that air pollution also directly harms our economies. Premature deaths from particulate matter cost Germany an estimated 132€ billion annually – almost 5 percent of its GDP. What’s more, on days when air quality is worse, more workers and students are absent, crime rates increase, and stock traders achieve lower returns.

Cleaning up our air would result in massive economic and public health gains. It could even disproportionately benefit socioeconomically disadvantaged communities who have historically suffered from the worst air pollution.

What is pollution and where does it come from

In lower concentrations, air pollution tends to be invisible, and only sometimes it is odorous. But what is it and where does it come from? For a quick primer on the different types of air pollution and their sources, I recommend this piece from the WHO.

In this article, I will primarily focus on particulate matter, or PM, which is a general class of air pollutant that consists of all natural and manmade particles in the air smaller than a given diameter.

PM10 has a diameter of 10µm or less (more than 100 times smaller than the diameter of a strand of hair), PM2.5 is no larger than 2.5µm, and PM1 is smaller than 1µm (that’s at most 10 times larger than the novel coronavirus).

Generally, the smaller the particulates, the more dangerous they are regarded, as finer particles can enter the bloodstream through the lungs. Particulate matter comes from countless different sources including combustion engines, private heating and energy systems, and industrial activities.

Unfortunately, many cities around the globe have poor air quality, and clearing the air is an enormous coordination problem. Businesses and individuals often do not consider the social costs of the pollution they produce.

To correct this failure, industrialized nations introduced landmark environmental regulations during the twentieth century, starting with the 1956 UK and 1963 US Clean Air Acts. Government-empowered environmental protection agencies monitored the air and enforced regulations that pressured citizens and industries to consider the social costs of their emissions. And these policies worked – they dramatically improved local air quality. Regions like Germany’s Ruhr Valley, London’s metropolitan area, and the Ohio-Pennsylvania Manufacturing Belt in the American Northeast no longer suffer from the killer smog episodes that plagued their inhabitants in the 20th century.

Post-industrialization has, however, brought new challenges. The public institutions that rescued cities from pea soup fogs are poorly equipped to tackle contemporary air pollution problems – truckers and automakers rig their vehicles with illegal software to cheat on diesel emissions regulations, over 23 European countries including Romania have failed to comply with EU nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter limits, and the stationary monitoring networks regulators built to track air pollution vastly underestimate spatial variations in air pollution.

What makes matters worse, environmental protection agencies are now facing simultaneous pressure from above and below. In North America, President Trump is gutting the US Environmental Protection Agency and rolling back air pollution regulations to the benefit of industrial interests. President Bolsonaro of Brazil similarly rejects pollution control in favor of environmental deregulation.

Community groups are pushing back. It seems they are dually skeptical of environmental regulators and legislators they fear have been captured by big industry.

In Germany, the non-profit group Environmental Action Germany (Deutsche Umwelthilfe) has filed a series of lawsuits against cities that failed to comply with EU air quality standards.

They independently monitor vehicle emissions to catch emissions-manipulating automakers, circumventing traditional regulatory channels.

Community environmental groups are fighting for the closure of industrial plants in Los Angeles, southern France, and in dozens of other cities with excessive toxic air pollution, where policymakers, industry, and regulators have failed local citizens.

The Push to Democratize Air Pollution Information

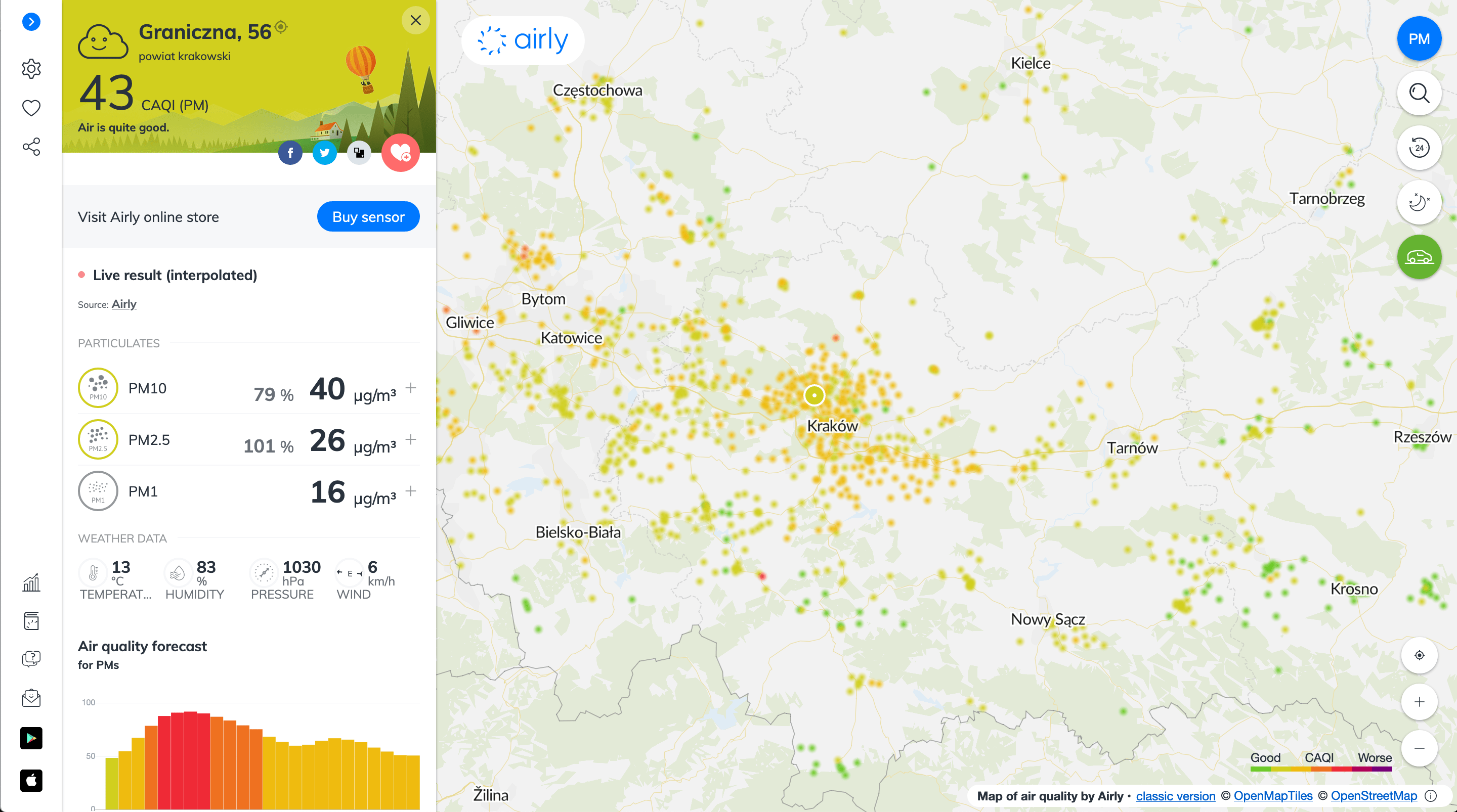

The immediate answer is that this future of ubiquitous air monitoring is already here – tens of thousands of people have recently purchased their own low-cost air pollution sensors and joined air quality monitoring networks such as PurpleAir, Luftdaten, and Airly.

They fix birdhouse-sized sensors to their windowsills and upload real-time particulate matter readings to online maps over a WiFi connection.

Over the past five years, these networks have grown rapidly, feeding an urban demand for better air pollution information. Each emerged as a unique blend of entrepreneurial spirit, grassroots environmental activism, and its own air pollution context.

Adrian Dybwad, founder of PurpleAir and electrical engineer, built his first sensor prototypes in 2015 to track dust billowing from an expanding gravel mine near his home in the American Southwest.

Early iterations caught on with friends and acquaintances affected by air pollution. Soon, a business was born.

Dybwad outfits the newest version, the $250USD PurpleAir II, with cheap and highly accurate Chinese PM10/PM2.5/PM1 sensors, originally developed for air conditioning systems.

In 2020, with over 3,300 PurpleAir sensors installed in California, Oregon, and Washington, the network provides crucial high-resolution, real-time air pollution information to those at risk from this year’s destructive wildfires and the harmful smoke they produce.

In 2018, I travelled to Stuttgart, where I sat in on one of Luftdaten’s monthly meetings at the city library. I was immediately struck by Luftdaten’s broad appeal and decentralized decision-making.

The two dozen attendees included digital natives, retirees, programmers, university students, political activists, cycling enthusiasts, and hobby scientists. The organization is run by volunteers, is registered as a nonprofit, and raises money through Kickstarter-like crowdfunding.

Luftdaten originally emerged from a citizen science hackerspace in Stuttgart, a city well known for fast cars and big industry but notorious for the worst air quality in Germany. Its DIY sensor kit is the cheapest of the bunch – a 25€ setup consisting of an Arduino microcomputer, another Chinese particulate matter sensor, a temperature and humidity sensor, a PVC piping joint, and a USB wall charger.

Luftdaten’s bottom-up approach met the political moment in Germany in late 2015, when the Volkswagen emissions scandal rocked public trust in the automobile industry and the institutions regulating it. Two of Luftdaten’s founding members travelled to science fairs, workshops, and conferences to seed the pollution sensor in communities around Germany like a pair of contemporary Johnny Appleseeds. Today, over 5,500 Germans publish their PM measurements to Luftdaten’s online map, with another 6,000 people uploading data in 70 other countries from all continents.

A different approach comes from Airly, a Polish start-up founded by engineers trained at the University of Science and Technology in Krakow, the economic center of the heavily industrialized, smog ridden Małopolska province.

Airly sells monitoring as a service. An initial setup fee of 100€ covers the installation of an air quality sensor that can measure nitrogen dioxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and PM. However, running the sensor costs a monthly fee.

Together with the device’s ability to send data over cellular networks, this business plan puts Airly in a unique position to supply local governments with entire networks of sensors.

Perhaps, from a startup born beneath the hazy skies of Krakow, this is a tacit acknowledgement that collective action, not just environmental consumerism, will be necessary to solve our air pollution problem.

More recently, two pioneering startups have pushed to the technical frontier in personal air quality monitoring, selling handheld, smartphone-connected pollution sensors for less than 200€.

Plume Labs and Atmotube designed these iPod Nano-sized devices as must-have gadgets for environmentally conscious customers. Accompanying apps map their daily air pollution exposure levels as they move, showing them where and when in their day pollution is worst.

The hope is that personal pollution information will nudge them to avoid air pollution, learn about its sources, and raise air pollution awareness among their peers. As of right now, their pollution data stays private though, unlike PurpleAir, Luftdaten, and Airly sensor data which is shared with the public.

Perhaps though, they can generate enough social and political noise as air quality ambassadors to a future when many more of us use mobile low-cost sensors.

Environmental Activism or Green Governance?

Utopians dream of a city with electrified vehicles and sustainable energy production. Heightened public air pollution awareness may be part of what brings us closer to this future reality where local air pollution is an afterthought.

If we extrapolate current trends into the future, personal air pollution monitoring may very well be ubiquitous in cities of tomorrow. Citizens, scientists, and policymakers will need better air quality data to make the political argument for cleaner skies.

But will personal air quality monitoring actually gain footing in our society and help us tackle our urban air pollution problems? A more pragmatic analysis paints several possible trajectories for the technology.

First, it is not clear how citizens themselves will respond to using pollution sensors. One of the aforementioned promises of this technology is that personal pollution information will motivate behavioral change – that, for example, a jogger will take a route with less air pollution or, perhaps, postpone their run to a time of day when fewer cars are on the road.

A recent study in the UK provides some startling insights into this type of behavioral response.

The researchers gave mobile pollution sensors to the parents of school children and asked them to accompany their children to school. For many parents, the sensors revealed high air pollution levels on their way to school – levels that turned out to be largely unavoidable, day after day, regardless of whether they took their children along main roads or alternate routes to school. It seemed that they could never get a step ahead of air pollution, and this alarmed the parents, evoking negative emotions – a lack of control over the environment and an inescapability of air pollution – that psychologists refer to as environmental anxiety.

This term is gaining attention as the mental health effects of other looming environmental crises, like climate disaster and catastrophic biodiversity loss, grow.

It is worth remembering that this is an early study with a specific sensor platform. Yet, it will be important whether sobering air pollution information paralyzes environmental action, whether citizens might overcompensate with overly cautious behavior, or whether political outlets will emerge for their anxieties.

A second dimension to personal air quality monitoring is whether citizens and policymakers will actually use collected pollution data to improve air pollution control.

Low-cost pollution sensors have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of air pollution. With a price tag at a fraction of government air quality monitors, personal air quality monitoring can densify our existing pollution control networks and provide pollution information at a ground-breaking spatiotemporal resolution.

This may be particularly important in urban settings, where air pollution levels can be up to eight times higher on one end of a city block than the other.

Attention has also drawn to so-called urban canyons – streets with tall, continuous buildings on either side that trap air pollution from vehicles. We certainly know too little right now about the air pollution hot spots and sanctuaries in the cities we live in.

Yet, despite recent technical progress in low-cost sensing, affordable sensor technology might not yet be the remedy.

Pollution readings from these devices suffer from considerable biases and shortcomings in field conditions. Moreover, citizen monitoring behavior may distort the readings and paint a radically different picture of air pollution than what is actually there. Citizens are, for example, less likely to monitor on rainy days when air pollution is lower. Their ability to monitor is also conditional on where citizens can walk in the urban landscape around them.

Data comprehensiveness may also depend on who purchases these devices. If other environmental goods (e.g. Priuses and solar panels) are any indication, citizen monitors are likely to have high income and high education levels. This may skew which neighborhoods have accurate, actionable air pollution information and thereby exacerbate existing pollution inequalities.

Governments may be hesitant to incorporate citizen data into the regulatory process for legal reasons. Personal sensor readings may, for example, lead to increased regulatory mistakes if non-representative readings are erroneously used to enforce environmental regulations, potentially negating the advantages of implementing these policies in the first place.

In a recent development, the US EPA introduced a layer of PurpleAir readings to its Fire and Smoke Map that informs citizens of nearby wildfires and outdoor smoke levels. The PurpleAir monitors are able to provide more localized and more frequently updated information than the government monitoring stations. Yet, the website clearly states their limitations:

This is a low-cost sensor that typically has unknown performance, siting, and maintenance. Data from permanent air monitors is higher quality than data from low-cost air sensors.

Data processing includes quality control screening, hourly averaging, and application of EPA correction factor and NowCast algorithm…neither the EPA, USFS, nor the U.S. Government may be held liable for any damages resulting from authorized or unauthorized use of the information.

Data users are cautioned to consider carefully the provisional nature of the information before using it for decisions that concern personal or public safety or the conduct of business that involves substantial monetary or operational consequences.

Calibration with government monitors, machine learning algorithms, and other technical solutions will likely improve data quality in the coming years, but they still may not resolve potential legal issues of involving citizens in the data collection process.

If widespread personal air quality monitoring exists in the city of tomorrow, it will likely take one of the following two forms:

- It will either remain in the realm of environmental activism, acknowledging that its data cannot be used for regulation but rather for generating helpful insights and building democratic pressure on regulators, businesses, and policymakers.

- Or it will be adopted by policymakers into formal air governance processes on the conditions of standardized monitoring protocols and sensor accuracy thresholds.

It may be that it only reaches the latter stage after a prolonged period in the former. Along the way to these new equilibria, personal air quality monitoring will have to grapple with its own sustainability (sensors have an expected lifetime under five years) and its environmental justice consequences.

Perhaps, by nature of its affordability, personal monitoring will rapidly evolve. Citizens will have to repeatedly invest in new sensors to replace their old ones, allowing them to measure new pollutants with increasing accuracy. In this case, personal air quality monitoring is future proof. What we’re learning about it today may be a peek into our near future.

The author

Alexander Dangel

I am a doctoral researcher at the University of Heidelberg's Research Center for Environmental Economics in Germany. My current research focuses on behavior and the environment, with an emphasis on citizens measuring the (unseen) social costs of air pollution. I am trained as an economist and I like to use geospatial analysis to understand how social phenomena move through space and time.

I also have an enduring interest in community networks and social entrepreneurship going back to my studies at Macalester College, where I co-founded a meal sharing network called NÜDL (think nonprofit "Uber for dinner" with a focus on building community). I am fascinated by the personal contributions to the community that I witnessed then and now study in my research.

Contributors

- Thank you to Claire Aichholzer, Alex Klopp, Philipp Bauer, Alec Balasescu, and Stefan Mako for reading drafts of this story

- Wanda Hutira - cover illustration

- Ștefan Mako - editor